The importance of the delay between infection and death in official statistics -- Part 2

Non covid deaths

A few days ago I posted an update on deaths with covid by vaccination status. In that post I stated that it is necessary to consider the vaccination statistics at the point of infection and not the point of death. Once this correction was applied much of the vaccine benefit suggested by the raw data disappeared.

But what about deaths for everything other than covid?

Well, we can’t simply apply the same correction. For the with-covid deaths it is necessary to adjust the data so that we're looking at the point in infection, not the point of death, but for other deaths there is no simple mechanism where a consistent delay can be applied; without a mechanism we just don’t have any reason to apply this adjustment.

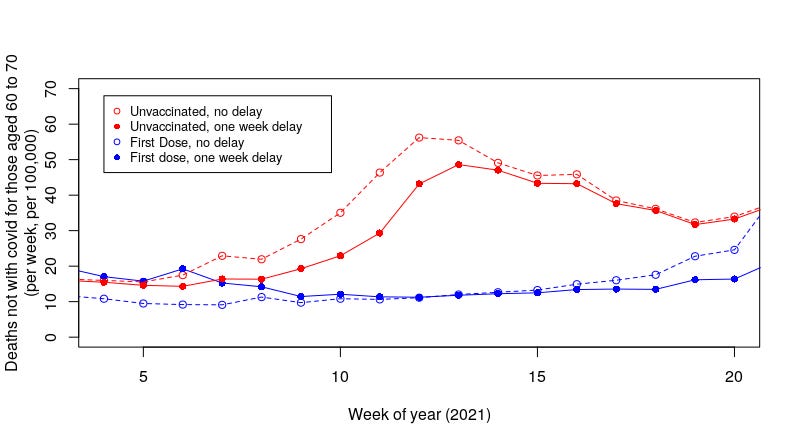

Nevertheless, I’d like to present a strange effect. We’ll just look at deaths not-with-covid for those aged 60 to 70 (the effect is seen for other age ranges, but this age range shows it best). If we apply a single week of delay in the data we get this graph:

The very interesting aspect to this graph is seen in weeks 4 to 8, before the main vaccination started in that age group. Before the correct was applied we had a notable difference in deaths per week per 100,000 between the vaccine and non-vaccine groups, but with the delay applied this difference falls out. This effect is rather pleasing statistically, as it removes an inconvenient difference between the unvaccinated and vaccinated groups at that point in time.

What’s more, we also now see a very slight decline in deaths in the vaccine group that mirrors (but with reduced magnitude) the increase in deaths in the unvaccinated group. This is also statistically pleasing, as it suggests that there is no overall change in the total number of deaths (the lower magnitude of the lowering of deaths per 100,000 in the vaccine group is seen because there are more individuals in the vaccinated group compared with the unvaccinated group).

I believe that this is what would be expected if the original hypothesis were correct; that they chose to not vaccinate those most likely to die, thus concentrating those more likely to die into an every smaller pool of unvaccinated individuals.

I believe that this, in a small way, adds evidence to support Norman Fenton’s hypothesis that a small delay in the deaths data, possibly arising from a reporting delay, might be creating an artefact in the data.

I note that the substantial increase in deaths not-with-covid in the unvaccinated group is still present in that graph (week 8 onwards). Given the difficulty in explaining this effect as a direct consequence of vaccination (the vaccines can’t affect those not vaccinated), I still believe that the data still supports the argument that those most likely to die were not vaccinated.

One aspect of these data has led to much discussion online — is there any data that suggests that the vaccines are causing deaths?

It is fairly clear that this is not visible in the data that I have presented. But then, should it be? As an example, if the vaccines were causing a 1 in every 100,000 to die per week across all ages we would have seen over 30 additional deaths per 100,000 in vaccinated individuals by now — that is approximately 0.03% of the vaccinated population or about 1:3,000 — this seems low but it would be an absolutely disastrous death rate for any medicine given to healthy individuals that would certainly result in immediate suspension of approval. But for deaths for those aged over 80 and for those aged 70 to 80 this number of deaths would be hidden amongst the large death rate that occurs in those age ranges anyway. For those aged 60 to 70 it is just possible that an additional death rate this large could be seen, but not if it occurred at the same time as there were changes in the distribution of the population, such seen in the vaccination only of those least likely to die. I’ll note again that I chose 1:100,000 per week as an example and I’m not suggesting that there is any evidence for a death rate of this magnitude — my point is that even a death rate this high would not be seen in the data.

And for younger age groups? It is very likely that a death rate of approximately 1:3,000 would be very visible in the data for younger age groups (those under 40). Unfortunately, by combining not with covid deaths into a very wide age range of 10 to 60, and also by mixing up when different ages were vaccinated, it is going to be very difficult to see such a statistical signal. This is one of the reasons why the ONS deaths data for those aged 10 to 60 is so frustrating.

It must be noted here that we have not excluded the possibility that the vaccines have had the effect of increasing deaths — it is merely that it appears impossible to detect any such effect in the data that the Office for National Statistics released.

You say, "it is merely that it appears impossible to detect any such effect in the data that the Office for National Statistics released.". This is a point that has been made before I'm sure, but if you look at the age range 14-44 in the ONS statistics, between the start of January and 17th September, the deaths in 2021 are 11890 and in 2020 were 10728, with the 10 year average of the same period being in the years 2010-19 being 10667. The 2020 figure is close to the 10 year average but the 2021 figure is over 10% higher. Obviously there may be many reasons for the increase in 1162 in the deaths in that period between 2020 and 2021, but a rise of over 10% of the average for the previous 10 years, does demand an investigation and an explanation. There is also a rise of 2391 between 2021 and 2020 in the age group 45-64, However this latter age group is obviously more vulnerable to Covid-19, and while the 2021 figure was 20% higher than the 10 year average, the 2020 figure was not far behind at 16%..

This set seems to understate England's entire population by 9-10 million - I find this fishy.